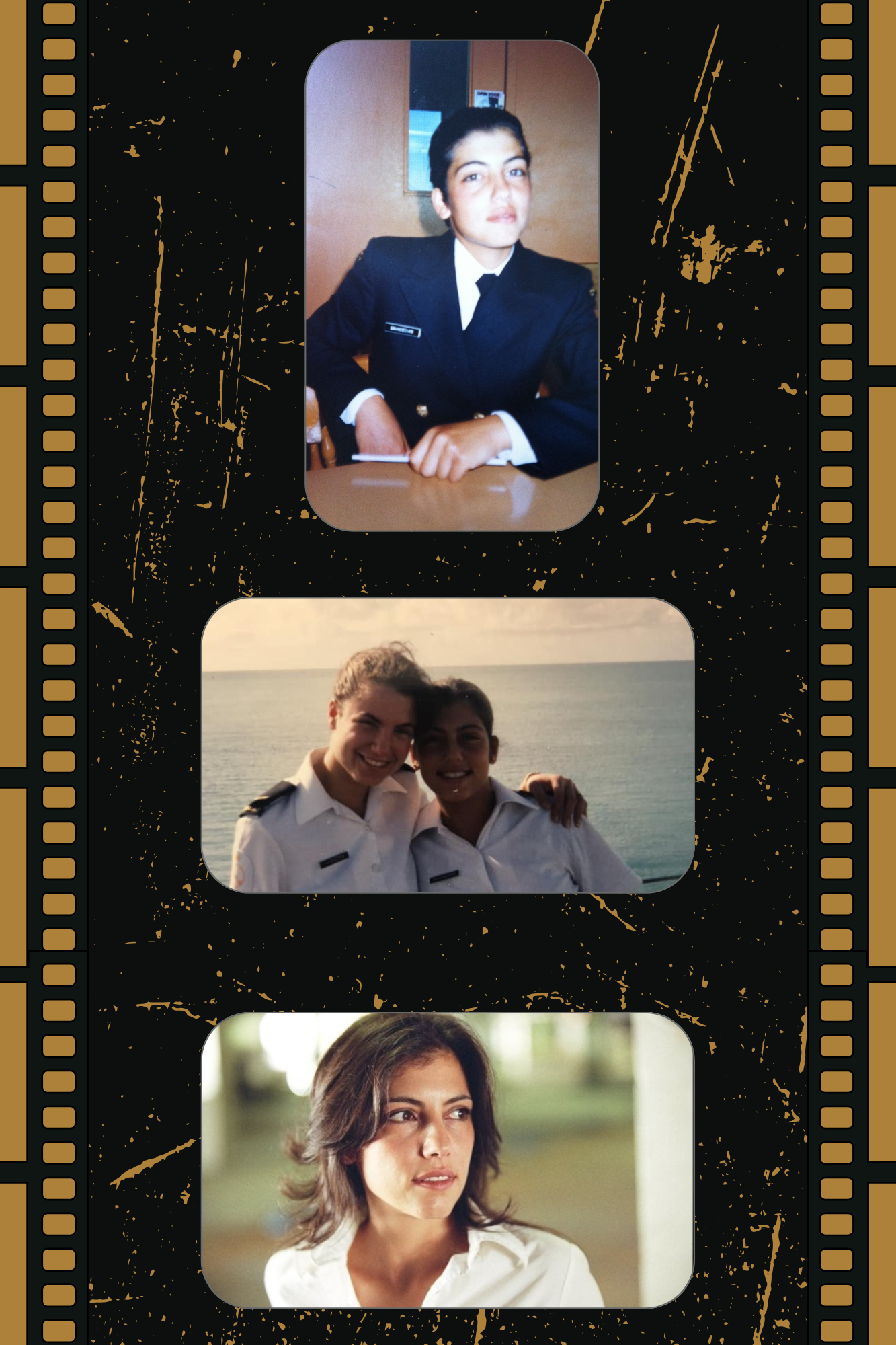

Many moons ago, when I first started out as an actress in Montreal, I was introduced to the world of Tennessee Williams. My varbed (an Armenian word for master or teacher) was Jacqueline McClintock, a brilliant teacher who had trained at the Neighborhood Playhouse in New York City. It was through her that I discovered the great American playwrights, and among them, Tennessee Williams. He didn’t just capture my attention; he captured my heart.

When I eventually moved to New York, I found The Strand, the famous bookstore filled with used books stacked high, bursting with history and plays waiting to be discovered. That’s where I started devouring everything Tennessee Williams. His plays. His short plays. His one-acts. His poetry. His biographies—both authorized and unauthorized. I traced his connections—whether real or perceived—to the Group Theatre and Sanford Meisner, always searching for the creative thread that linked these great people.

But what fascinated me most about Tennessee Williams was how his works evolved. He didn’t just sit down and write a masterpiece in one go. No, his plays were born from something smaller, then transformed, then refined, then rewritten—over and over—until they “fixed” Tennessee’s life enough.

Take The Glass Menagerie, for instance. Before it became the full-length play we know today, it was a one-act called The Gentleman Caller. And before The Gentleman Caller, it was a poem titled The Girl in the Glass. Through all my reading, I reverse-engineered his creative process and discovered that The Glass Menagerie had its origins in this poem.

He was notorious for reworking his endings. He struggled for closure—not just in his writing but in life. Take Summer and Smoke, for example. Alma’s “end” never quite sat right with him. Even though the play had been published and performed, he later wrote an alternate version of it, titled The Eccentricities of a Nightingale. Same characters, same world, but Alma was different this time—stronger, changed. That was Tennessee, always searching for the right ending, for “fixing it” in the play meant fixing himself somehow.

The Silent Rivalry with William Saroyan

Beyond his own struggles, I realized that Tennessee was fiercely competitive—particularly with William Saroyan. He was jealous of Saroyan’s success, but more than that, he was obsessed with figuring out how Saroyan wrote.

Tennessee studied his rival’s work and one day, he finally figured it out: every character Saroyan wrote was a version of himself. Saroyan was like a multiplying rabbit—each of his characters was simply him at a different stage of life. He could be the six-year-old in one scene and the wise old man in another, but they were all Saroyan. Tennessee found relief in figuring this out, as if he had discovered Saroyan’s secret sauce! He noted this revelation with exclamation points in his writings, like he was proud of himself.

His own approach was different. He wrote about loneliness. From loneliness. From yearning. From a deep fear of being alone. His plays were drenched in symbolism. His worlds were filled with signs and omens, moments where something as small as a dying fire in a fireplace could signal the loss of a fleeting opportunity for love.

The Symbol of a Dime

Tennessee Williams was a letter-writer. Over the years, I noticed how his signature evolved. At first, he signed letters as Tennessee. Then, as time passed, he shortened it to Tennie. Later, he signed simply as Ten. And eventually, it became just a number—10. A dime. A simple coin.

And that stuck with me.

Somehow, dimes started appearing in my life at the strangest moments. Whenever I doubted myself or felt lost, I would find a dime. Not a penny, not a quarter, not a nickel. Always a dime. A sign from Tennessee telling me everything would be okay.

It sounds crazy, I know. But the dimes kept showing up and still do. In the most random places. At airports, in different locations, I would choose a random chair to sit in—and there would be a dime on that very chair. I would stop walking, look down, and there it was—a dime. It happens all the time, even in my house, at other people’s homes, on the street, in a store. Random areas where it’s sticking out like a sore thumb. Like literally in the middle of a chair that I go to sit in.

The dimes have been following me for years.

The Final Act

Though I don’t read Tennessee Williams as much these days, he was a defining part of my life—especially during my formative years as an actor. His words shaped me. His struggles fascinated me. His hunger for love and connection mirrored my own.

So much so that visiting his grave in St. Louis is still on my bucket list. I read somewhere that he wanted his ashes scattered at sea, like his favorite poet, Hart Crane—whom I also read because Tennessee read him. However, his brother didn’t allow for that, and he was buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis instead.

And that’s the thing about Tennessee Williams. He was always searching—for the right words, the right ending, the right life. And in his search, he gave the world some of the most beautifully broken characters ever written.

He also gave me a quiet kind of reassurance.

Even now, when I find a dime, I smile.

Because I know Tennessee Williams is still watching over me, telling me with his smile that everything is going to be okay.